This article was originally published on Medium under a similar title.

Crash Course: More Content, Less Words (or Flash Fiction in about 600 words)

Whenever I assign a 1500–2000 word essay in my First Year Writing courses, there is a collective groan. Many students feel that they can say everything they need to say in much less than that. But experienced authors realize that clearly communicating a concept is actually harder with less words. Indeed, the hardest essay I ever wrote as a student was an 800 word essay on understanding complex gender criticism in Mary Shelly’s Frankenstein. The sweat… the tears… the removed signal phrases to get under word count. *insert facepalm emoji here*

So, it’s no surprise that in my Advanced Fiction courses the collective groan comes when I assign smaller word counts. Indeed, my students routinely struggle to keep their story submissions within the assigned perimeters of a couple thousand words.

Sure, there’s plenty of work to write an argument properly, but when dealing with creative writing, we’re introducing whole people and settings that our readers have never met before (or if they have that we need to establish accurately). We have a lot of work to do. Introduce a character, a goal, a conflict. Work the reader through understanding why that character is struggling to reach that goal and why they make the decisions they do. Make it relatable. Clearly bring to life the world and emotions around them. Offer something satisfying in the end. And if you’re writing in a genre that requires building a whole new world, there’s even more information to communicate!

But if we think through some of our favorite quotes or scenes from some of our favorite works, we often find that we’re most moved by quick punches of emotion or realization. Pithy summaries of complex concepts. Metaphors that shake our core with experiences that far out weigh their word count.

Now, sure. Those stories have the benefit of thousands of words of context leading up to those moments. But — is it possible to write something just as brief and meaningful in a standalone piece? In merely 500–700 words?

Could trying to write a piece in that length teach us more about language and character and reader comprehension than we may ever learn revising and re-revising a piece thousands of words longer? Absolutely.

That’s the beauty of flash fiction.

If you’re interested in learning more about the benefits of creative restraints, I recommend you check out my article “Crash Course: Flash Fiction in 1000–1500 Words.” This may actually be a better place to start if you’re nervous about writing short works at all.

But today, we’re looking at stories 500–800 words in length. How to get shorter than short? There’s plenty of tricks and lessons for writing pieces of 1000 words or more that certainly still apply here, and if you have not already reviewed them, I encourage you do. But when we’re trying to knock even shorter, it’s vital that we also become efficient with language and plot. That we learn to communicate more content in less words and how to decide what doesn’t need to be communicated at all.

Opening Activity: More Content, Less Words

Let’s start with a simple revision activity. For each of the scenes below, try to remove words, without sacrificing content. These lines are purposefully a scoosh overwritten to more easily illustrate the concepts.

A) The dog was very large and very shaggy, and it was panting heavily with its mouth hanging open and drool dripping from both sides of it jaw. (27 words)

B) The boy looked sadly down at his mint chocolate chip ice cream cone which was sitting upside down at his feet. The girl in the pink headband laughed in a rude way, but she stopped when she saw the tears slowly dripping down his face. She put her arm around him and offered him a taste of her chocolate ice cream cone. (62 words)

It might take you a few tries, but focus on each word and what we’re learning from it. Will one word properly replace a short phrase? Could the feeling or connotation of another word more quickly capture the tone of the moment? Or even, add a tone that isn’t there currently?

When I did this activity in a live classroom, students were able to get scene A down to 8–13 words without losing any content. Scene B we could cut nearly in half without losing content, and could even lessen the word count and add more detail. However, we found that any word count below 25 started to remove detail.

Here is an example of B with less words but more dynamic content:

Kersplat. The boy’s mint chocolate ice cream cone hit the concrete. Sadness overwhelmed him. The girl in the pink headband snickered — until she saw the tears falling from his chin. She cradled his shoulders, offering up her chocolate cone. (38 words)

So what has changed? Words were cut, but was content also added?

Let’s take a look.

In this version, we’ve cut 24 words, but have shown an additional action — the cone itself falling. In the original, the cone had already fallen. We also now know that the cone hit concrete which is more specific than the original “ground” (added content). His sadness is more palpable as it “overwhelm”s. The girl’s actions are also more specific as she “snickers” and “cradles his shoulders.” These actions are easier for readers to visualize. Readers are also more likely to visualize them in more similar ways. In other words,“a rude way” leaves more room for interpretation than “snickers” in the same way that “she put her arm around him” does not state where her arm is located (waist, shoulders?) or how quickly or with what type of care the action is performed (quickly, gently, suddenly?). While we’ve added detail and a bit of action/content, we’ve also removed unnecessary explanations to make use of reader assumption as well. “But she stopped when” is replaced with the more efficient “ — until.” Readers understand that the previous action (the snicker) has been brought to a sudden stop. Likewise, we make use of reader assumption when we say “offering up her chocolate cone.” The word offer implies the act of sharing or tasting as readers assume that is what one would do with an ice cream treat that was “offered up.” It’s quick, common, and to the point, reader imaginations providing the rest. You’ll note that “chocolate cone” also skips the words “ice cream” as readers already know we’re dealing in ice cream, and the reminder is unnecessary.

Using reader assumption about basic actions is a similar concept to skipping a dialogue tag, which is advice you may have heard before and which we see employed commonly, even in longer works. Readers understand that quotes signify speech or something spoken. So, unless it is unclear who is speaking or we need to know specifically how it was spoken, we can often skip the tag altogether. Skipping “they said” also saves 2 words per dialogue line, btw.

Understanding how readers move through a text and how different words can illicit different feelings and visuals is a vital part of writing concisely. It’s learning to recognize when we’re writing things we don’t need to (She turned the handle to open the door v.s. She opened the door) or that aren’t vital to story comprehension, and when we’re choosing words that strike the right general action but actually tell us less about what the character is experiencing (He looked at the girl v.s He glared at the girl vs He stared at the girl vs He noticed the girl.).

Stephen King in his memoir/writing guide On Writing offers an excellent exercise where he asks readers to imagine a rabbit in a cage on a table with a red table cloth. The rabbit is white with a blue eight on its back, and it’s munching on a carrot. He then asks if we’ve all seen the same thing. I run this exercise with my writing students often, and they all nod and say yes, we’ve seen the same thing. Until King asks us if the cage was glass or wire? If the table had a fancy table cloth with lace or a plain table cloth. If it was cloth or plastic. Not to mention, where is this table? A kitchen, a stage, a basement? How big is your rabbit? How much carrot has been eaten?

Repeating the whole exercise here is not necessary except to say, it is very good practice to look at your work and ask not only what is open to interpretation but what readers will assume based on context. For instance, we all assume the cage is see-through because we know we can see the rabbit. We don’t need to be told it is one of the basic cage constructions. However, knowing if the cage is wire, bars, or glass could be important later, or just be important if the aesthetic of that moment is important to you as an author. Does it ground us more? What purpose is it serving?

As with most writing advice, there isn’t an always-never rule here. It’s about choice and actively, consciously making educated choices about what we keep and what we cut. Where we add and purposefully withhold.

In poetry and short pieces, we often talk about words doing work. That every word must be doing an important job, and words that communicate more or phrases that communicate much are “heavy lifters.” This doesn’t mean to avoid all simple language. But it does mean to think about the work your words are doing. Is a simple word avoiding a complex moment or banal explanation that doesn’t need further elaboration? Is this complex word better for your style and the emotion of the moment? Does a single word tell us more about what is happening and how than this phrase? Will your reader know the word?

As an author, you’re controlling your reader’s imagination. King calls it telepathy, even though that’s not strictly true. But, every word they read, they imagine. And each word brings with it connotations both personal and societal. We culturally and contextually also make assumptions about situations and characters. Knowing what those assumptions might be and how to create new assumptions within your readers, is a key step to understanding what words or details can easily be cut — but also, which details will bring forth a very specific image or change the feeling of an entire scene at a very low word count cost.

When writing a story in only 500–800 words, efficient word use is certainly important, but we can also use reader assumption and quick context to compress the plot of a story.

Understanding Plot: Does it all need to be there?

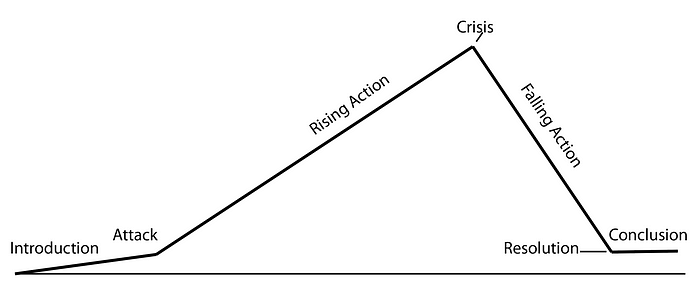

Flash Fiction can certainly include full story arcs. That said, many start right before or even right at the climax and have only enough of a resolution for the readers to digest the change that has happened. Back story or context may be less important or merely implied. Or, you may see condensed stories that are more fairy tale like in their narration, covering larger spans of time in quick summaries.

The shorter the story, the closer you start to the Crisis or Climax. This is a common way to condense a story.

However, other creative methods can be used to to allow for more of the plot to be included through implication, such as using form to instigate a pre-existing context. For instance, you may choose to tell your story in a letter format or a series of text messages. Such structures already give the reader the sense of spying into the life of someone and information about why/how the information is being formed. They also don’t expect to know everything from the past and are already in detective mode to see what they can learn from the clues provided.

You can also use stories that offer detail and commentary that appear to be about an single individual, but are really a story about a larger group, meaning that much of our understanding comes from what we already know about society. Take for instance, Jamaca Kincaid’s “Girl” which is only 700 words long. It’s packed full of specific commands and details about a single individual, but the meaning and impact of the story comes from our understanding of the real world. Much is implied and simple statements become heavy with additional meaning, particularly when they contradict one another.

The shorter the story gets, the more it can also walk the line between prose poem and story, so with shorter stories you will also see a shift in focus to descriptive language and detail, one impact-laden scene as opposed to multiple scenes. However, the same rules you would apply to any fiction still apply if you truly want Flash Fiction and not a poem or vignette. A full story must still be communicated. It’s just a question of how much of it is actually on the page, and how much is quickly established or implied.

Suggested Reading:

500 words is kind of a magic number in flash fiction, and so you’ll see many journals and contests that request this number specifically or use it as a maximum. That said, it’s easy to find stories that explore slightly above and below that range in online publications. So, let’s look at some examples.

This is a great page to explore some wonderful work from young writers. They’re awarded Scholastic Awards for their flash fiction, which tends to hit right around that 500 word sweet spot. I think it is important to look not just at established, published authors for guidance, but at the work being actively created now, by authors like you. There’s a treasure trove of inspirational work out there. And it makes the goal feel more attainable to recognize it isn’t something that only Hemingway, or whatever big-pants name, can pull off.

“After the Hysterectomy” by Ira Sukrunguang: This story is nonfiction and is actually a little over 600 words but dives into the heart and mind of a man who married without children. There is some beautiful word choice going on here and it shows how examining an internal conflict can be a good frame and crisis for a flash fiction plot. To see more flash nonfiction from Brevity go here: brevitymag.com

“Lions in the House” by Beejay Silcox won 2nd place in The Master Review’s Blog 2017 Flash Fiction Contest. Five years later it’s 648 words have stayed with me. The situation is unusual yet relatable. Focused and descriptive. It’s worth noting that the contest allowed for more words. Silcox didn’t need them. You can view other Flash Fiction contest winners writing below the 1000, and often below the 800 word mark for this contest here.

Exercises:

Time to try your hand at a 500–800 word story. Remember what you liked or didn’t like about the stories above, and choose one or more of prompts below to practice.

Prompt A: Re-tell a classic tale (a fairy-tale, an important moment in history, a recognizable story like Romeo & Juliet) in only 500 words. Knowing an existing plot and deciding how to condense it or how to start later and still make sense — or even how to use reader assumption about the original, can help you better identify how to do this with your own plots.

Prompt B: Tell a story in 500 words that is framed as advice that is being given or told to someone else. Something like “Girl” posted above or “An Emotional Wreck’s Guide to Recovery” from the Scholastic Award site. When working in a form that we naturally expect to tell us a lot in a little, we set your readers up for all sorts of assumptions. When offering an audience or using societal expectations and concepts, we allow or readers to quickly fill in context and add additional meaning to our singular details. It also puts the pressure on you to remain concise as the form demands it, and puts you in a voice that may say telling things about the past without belaboring them.

Prompt C: Take a short story you’ve already written. Maybe even a longer Flash piece, and make it shorter. Much like we did with the sentences in the opening activity — but with a whole story. Can you get it down to 600? 500? 300?

Tip: When you’re about 200 words from your limit, stop and look at what you have. Can you end the story in 300 more words? Do you need to start over? Or maybe, you just need to cut from the beginning. Sometimes we give unnecessary or repetitive detail in the beginning of the story because we ourselves are getting to know the setting and characters, but some of that detail could be moved and/or communicated in more concise ways — or may not be necessary at all. As writers, sometimes we need to write 3000 words to realize only our final 600 were necessary. We also tend to repeat concepts and phrases, or show the same concept in multiple ways. In longer works this can be useful to subconsciously drive a point home. In shorter works, it’s likely best just to use the strongest example — or purposefully amply your repetition in smaller ways. But make this a conscious decision. And always remember: just because you had to write it to know or understand it, doesn’t mean your readers have to read it. They could learn it a different way, or may not need to know it at all.

Takeaway Thought:

In flash, you can leave your readers wanting to know more, but you should never leave them needing to know more. Knowing what is excess and what is necessary is the first step to shorter writing.

As always, you may decide that this word length isn’t the length for you. Still, you can take what you’ve learned from these exercises and apply them to longer works. Imagine a novel where every page has hard working words and is making excellent use of reader assumption.

Keep practicing, keep trying new things, and until we meet again, happy writing!

If you enjoyed this Crash Course, please keep a look out for more Crash Course articles on writing flash and other writing tips.

Comments

Post a Comment